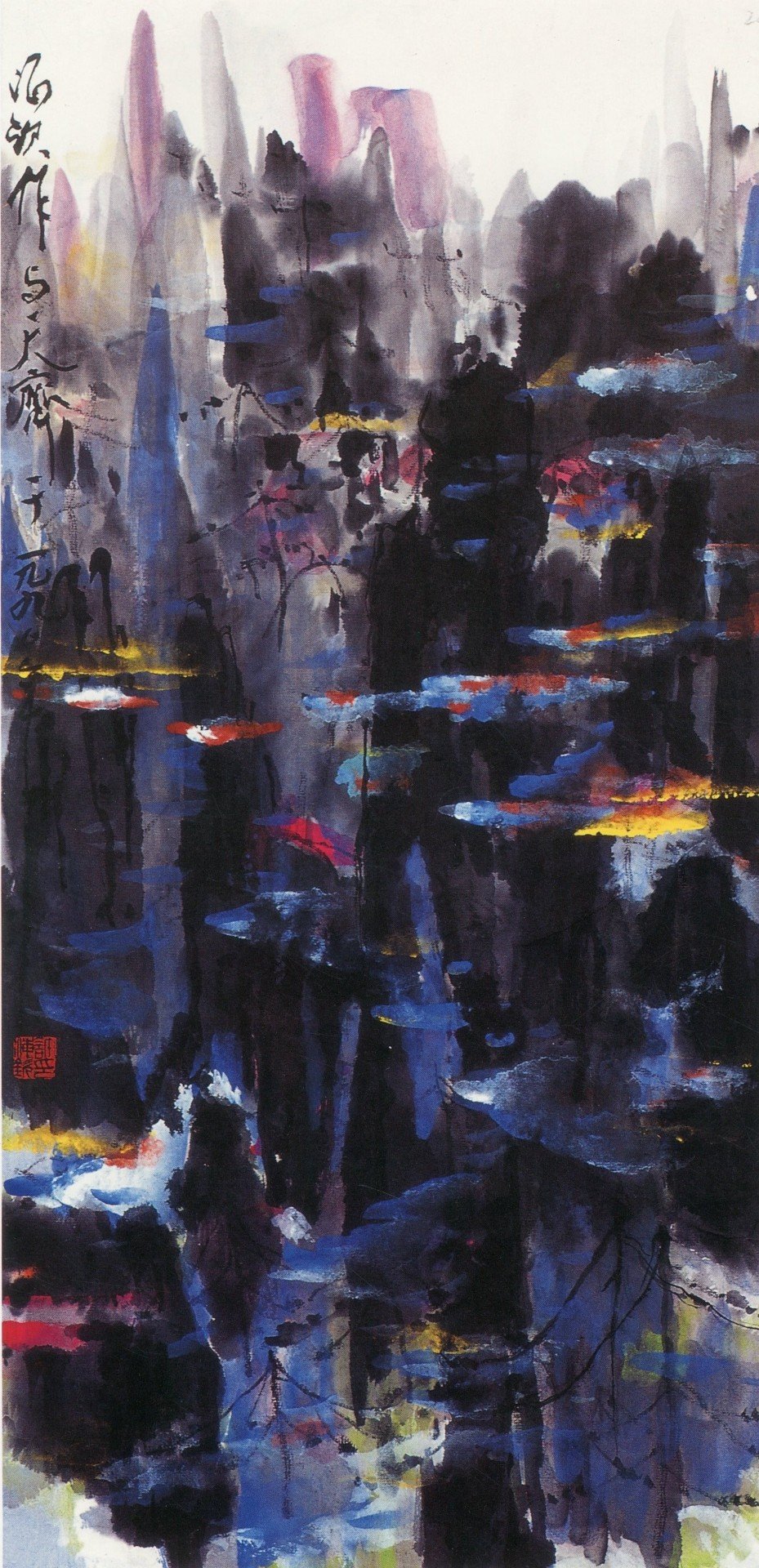

一、藝術家姓名 アーティスト名: 許海欽 Xu,Haiqin

二、作品圖片 作品画像:

三、作品名稱 作品名: 與天齊 天と並ぶ(てんとならぶ)

四、作品尺寸 作品サイズ: 46×140cm

五、作品媒材 作品の素材(媒材): 水墨畫 水墨画(すいぼくが)

六、年代 制作年: 1990年

創作理念:

《與天齊》是許海欽教授旅居韓國時所作一系列山水作品之一。1990年交換教授於韓國馬山慶南大學,許教授經常利用課餘閒暇之際,探訪韓國的名山古寺廟。造訪海印寺時,見其寺廟深深地座落半山腰上,當日晨曦映照之下,五彩斑斕的春霧瀰漫,海印寺若隱若現,增添許多古寺的神秘空靈之美。他透過寫生的工夫,意識物外之趣,追求遺形寫意寫趣,再來更上層樓,悟物體的空性,最終許海欽想要傳達的訊息就是神與靈的境界了。因此畫面著色採濃墨重彩,筆觸頓挫有節奏感,構圖布局用重山疊翠高聳入雲霄,更打破傳統,不作太多留白,以蒼松喻隱者的風骨,襯托出畫家欽慕高仰佛門勝地。全幅畫作如春蠶吐絲連綿不斷,筆酣墨暢如行雲流水般,一氣呵成。許教授寫其尋幽探訪海印寺時,感受到「只在此山中 雲深不知處」的是詩境,藉由此畫描摹得淋漓盡致情深意切。許海欽教授一生熱愛老子的哲學美學觀和莊子逍遙遊自由自在的思想。他畫山水深不可測,如浩瀚的星塵無邊無際。他在宣紙上,用抽像概念畫出金木水火土風雷電日月星塵,借此傳達形而上無無明大智大慧。

7/18 2025 海月堂隨筆

**Artistic Concept**

**“Equal to the Heavens”** is one of a series of landscape paintings created by Professor Hsu Hai-Chin during his time living in South Korea. In 1990, as an exchange professor at Kyungnam University in Masan, Professor Hsu often took advantage of his free time to visit Korea’s famous mountains and ancient temples.

One such visit was to **Haeinsa Temple**, nestled halfway up a mountain. Bathed in the morning light, the temple was shrouded in vibrant spring mist, appearing and disappearing in a dreamlike veil that lent it a mystical and ethereal beauty. Through his sketching practice, Professor Hsu sought to capture not just the form but the spirit beyond appearances—expressing the poetic essence of nature, and ultimately ascending to a philosophical reflection on the emptiness of form. His goal was to convey a realm of the divine and the spiritual.

The painting employs **rich ink and vibrant colors**, with bold, rhythmic brushstrokes. The **composition features layered mountain ranges soaring into the sky**, breaking from traditional norms by forgoing vast empty spaces. Ancient pines symbolize the noble character of reclusive hermits, underscoring the artist’s admiration for sacred Buddhist sites. The entire painting flows seamlessly, like a silkworm spinning silk, or like clouds and water in motion—completed in one fluid, expressive breath.

In depicting his mystical visit to Haeinsa, Professor Hsu beautifully conveys the poetic sentiment of the verse:

*“Only within these mountains,

Where clouds are deep,

Is the place unknown.”*

Professor Hsu Hai-Chin spent his life immersed in the philosophical aesthetics of **Laozi** and the free-spirited worldview of **Zhuangzi’s “Carefree Wandering.”** His landscapes reflect vast, unfathomable realms—like the infinite dust of stars. On xuan paper, he uses abstract forms to paint the **elements of metal, wood, water, fire, earth, wind, thunder, lightning, sun, moon, and stardust**, conveying a profound metaphysical wisdom beyond the visible.

*— Notes from Haiyue Studio, July 18, 2025*

日本語訳

創作理念:

《天に斉(ひと)し》

《天に斉し》は許海欽(きょ・かいきん)教授が韓国に滞在していた時期に制作した一連の山水作品の一つです。1990年、韓国馬山(マサン)の慶南大学(キョンナムだいがく)で交換教授として教鞭を執っていた許教授は、授業の合間を縫って韓国の名山や古刹を頻繁に訪れていました。海印寺(ヘインサ)を訪れた際、山の中腹に深く佇む寺の姿を目にしました。その日の朝、色とりどりの春霧が立ち込め、日の光を受けて輝く中、海印寺は若隠若現し、古刹の神秘的で空霊な美しさを一層引き立てていました。

教授は写生を通じて、物事の外にある趣を意識し、形を離れて意図や趣を描き出すことを追求しました。さらに一歩進んで、万物の空性を悟り、最終的に許海欽が伝えたかったメッセージは、神と霊の境地でした。そのため、画面の彩色は濃墨重彩(のうぼくじゅうさい)の手法を用い、筆致には頓挫(とんざ)とリズム感があり、構図は重なり合う緑の山々が雲を突き抜けるように高くそびえ立っています。さらに伝統を打ち破り、多くの余白を残さず、蒼い松をもって隠者の風骨を表現し、画家が仏教の聖地に対して抱く敬慕の念を際立たせています。

全幅の絵は、春の蚕が糸を吐くように途切れることなく続き、筆は勢いよく、墨は流れるように、まるで行雲流水のごとく一気呵成に描き上げられています。許教授は、幽玄なる海印寺を訪れた際に感じた「只だ此の山中に在り、雲深くして処を知らず」という詩の境地を、この絵画を通して余すところなく、深く情感を込めて描き出しました。

許海欽教授は生涯にわたり、老子の哲学的・美学的観点と、荘子の「逍遙遊」に見られる自由自在な思想を愛しました。彼が描く山水は奥深く、まるで果てしない広大な星屑のようです。宣紙の上で、彼は抽象的な概念を用いて金、木、水、火、土、風、雷、電、日、月、星、塵を描き出し、それによって形而上的な、無明のない大いなる智慧の境地を伝えようとしたのです。

2025年7月18日

海月堂随筆

---

翻訳に関する注記 (Translator's Note):

- 許海欽 (Hsu Hai-chin): 日本語では一般的に確立された読み方がないため、中国語の発音に近い「きょ・かいきん (Kyo Kaikin)」としています。

- 海印寺 (Haeinsa): 韓国語の発音「ヘインサ」をそのままカタカナで表記しました。日本の寺院にも同名の「かいいんじ」が存在するため、区別を明確にしました。

- 慶南大学 (Kyungnam University): 韓国語の発音に近い「キョンナムだいがく」としました。

- 濃墨重彩: 日本画や中国画で使われる、濃い墨と鮮やかな色彩を用いる技法を指す言葉です。

- 只だ此の山中に在り、雲深くして処を知らず: 唐の詩人、賈島(かとう)の詩「尋隠者不遇(隠者を尋ねて遇わず)」の一節を引用したものです。

許海欽

福建詔安人,來自書香世家,自幼受文學藝術的熏陶,精通書畫。畢業於美術、中文、藝術與哲學神學研究所,並獲得碩士學位。曾赴美、韓交換教授,並於1966年獲得「第十二回全日本書道展」優秀榮譽賞狀。1998年,他獲得「中國文學藝術界名人作品展示會」金鼎獎。1989年,應台灣行政院邀請,代表國家在倫敦、巴黎、紐約、華府等九大歐美城市巡回舉行個展。1992年,應北京國務院邀請,於北京、南京、上海的國家美術館舉辦個展。

許海欽致力於中華藝術的創新發展,他的作品展現出獨特的神韻,並追求藝術的極致之美。藝術界譽為「文人畫家」。

《江山如畫》 說明:此畫呈現東方繪畫深邃神秘的情境,並融合了西方後印象派大師塞尚及野獸派創始人馬蒂斯的繪畫理念。以奔放的筆觸、濃厚的色塊,顛覆傳統,創造了水墨畫的新里程碑。

Xu Haiqin

a native of Zhao'an, Fujian, comes from a family of scholars and was immersed in literature and art from a young age. He is proficient in both calligraphy and painting. He graduated with a master's degree from the Institute of Fine Arts, Chinese Literature, Art, and Philosophy & Theology, and has taught as an exchange professor in the United States and South Korea. In 1966, he received the Outstanding Honor Award at the "12th All-Japan Calligraphy Exhibition." In 1998, he was awarded the Golden Ding Award at the "China Literary and Artistic Figures Exhibition." In 1989, invited by the Executive Yuan of Taiwan, he represented the country in a solo exhibition tour in nine major cities across Europe and the United States, including London, Paris, New York, and Washington D.C. In 1992, at the invitation of the State Council of China, he held solo exhibitions at the National Art Museums in Beijing, Nanjing, and Shanghai.

Xu Haiqin has dedicated his life to the innovative development of Chinese art. His works showcase unique charm, striving for the ultimate beauty in art. He is honored as a "Literati Painter" in the art world.

"Rivers and Mountains Like a Painting" Explanation: The painting presents the profound and mysterious atmosphere of Eastern art, while incorporating the artistic philosophies of Western Post-Impressionist master Cézanne and Fauvism founder Henri Matisse. With bold brushstrokes and rich color blocks, it subverts traditional methods, creating a new milestone in the realm of ink painting.

許海欽(Xu Haiqin)

は、福建省詔安出身で、書香の家系に生まれ、幼少期から文学や芸術に親しみ、書画に精通しています。美術、中文、芸術および哲学神学研究所を卒業し、修士号を取得しました。アメリカと韓国で交換教授として活動した経験があり、1966年には「第12回全日本書道展」で優秀賞を受賞しました。1998年には「中国文学芸術界名人作品展示会」で金鼎賞を受賞しました。1989年には、台湾行政院からの招待を受け、国を代表してロンドン、パリ、ニューヨーク、ワシントンなど、欧米9都市で個展を巡回開催しました。1992年には、中国国務院の招待を受け、北京、南京、上海の国立美術館で個展を開催しました。

許海欽は、中华芸術の革新と発展に尽力しており、彼の作品は独自の神韻を表現し、芸術の極致の美を追求しています。芸術界では「文人画家」として評価されています。

『江山如画』の説明:この絵画は、東洋の絵画における深遠で神秘的な情景を表現しており、また、西洋の後印象派の巨匠セザンヌと野獣派の創始者マティスの絵画理念を融合させています。奔放な筆使いや濃厚な色塊を用いて、伝統を覆し、墨絵の新たな金字塔を築きました。

![[アジア平和芸術,台日書畫水と墨の魔法]展 官方網站上線](https://rumotan.com/images/sampledata/kanagawa/kanagawa2.png)